The use of Open Source technology has been growing in space exploration and advocacy movements. The reasons and benefits are manifold. It lowers cost. It gives companies or organizations direct access to the internals of the hardware and software. It allows you to leverage the power of a very large community of participants to help develop solutions. Space organizations, from big to small, are embracing this path forward.

The first instance I am aware of where this is explicitly true was in 2013, but that may have simply been the first one brought to the public’s attention. The reason for the change came from a security breach at the International Space Station.

In 2013, the ISS replaced all it’s Windows software with Linux. It was replaced by Debian 6 to be specific. It turned out that the security weaknesses of Windows XP let someone bring a copy of the W32.Gammima.AG, which was a gaming worm designed to gather logins from gamers. Fortunately, this worm didn’t actually pose a threat to the ISS, but it makes the weaknesses of Windows systems apparent. A complicating factor of using Windows was that it extended support and development outside of NASA and the partners of the ISS. The use of Linux, as a model example, shows that the need to be able to access the inner workings of software without having to worry about licenses and proprietary is very important for space applications. Hence, open source will be crucial to future expansions.

The space station even has it’s own supercomputer powered by Linux. In 2017, Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE) and NASA installed and activated an Apollo 40 server with a high-speed HPC interconnect running Linux on the space station. An interesting deviation from general practices is that this system IS NOT ruggedized. The goal is to develop a fault-tolerant system that can work within higher radiation settings and other dangerous conditions such as solar flares, unstable power supplies, micrometeoroid impacts, and more.

In another example, we have SpaceX’s ubiquitous use of Linux across all systems. We can find examples of Linux, and therefore, open-source principles in many projects that SpaceX works on. According to Robert Rose, who spoke at the 2013 Embedded Linux Conference is used in most places at SpaceX.

The Falcon, Dragon, and Grasshopper vehicles use it for flight control, the ground stations run Linux, as do the developers’ desktops. SpaceX is “Linux, Linux, Linux”, he said.

SpaceX Preps Self-Driving Starlink Satellites for Launch

The use of Linux at SpaceX was expanded when the Starlink Project was developed and those satellites now use a multiprocessor enabled version of Embedded Linux. If SpaceX recognizes the advantage of using open-source software across such a wide variety of systems, it only makes sense to look at it for LUF purposes.

Of course, it’s not just open-source software that’s making its way into space applications. Open-source hardware is being developed for multiple uses in the space field. A lot of the progress is based around single-board computers such as the Raspberry Pi and the Arduino. This is a beginning, but since these boards are based on the ARM family of chips, they’re technically semi-open-source. However, let’s explore some of these open-source projects.

- SkyCube (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SkyCube) was developed after a successful crowdfunding drive. It was launched to the space station on January 9, 2014. It was deployed on February 28, 2014, and met it’s fate, as planned, on November 9, 2014. The design followed the CubeSat standard and was used to send images back from space until it was destroyed on atmospheric re-entry.

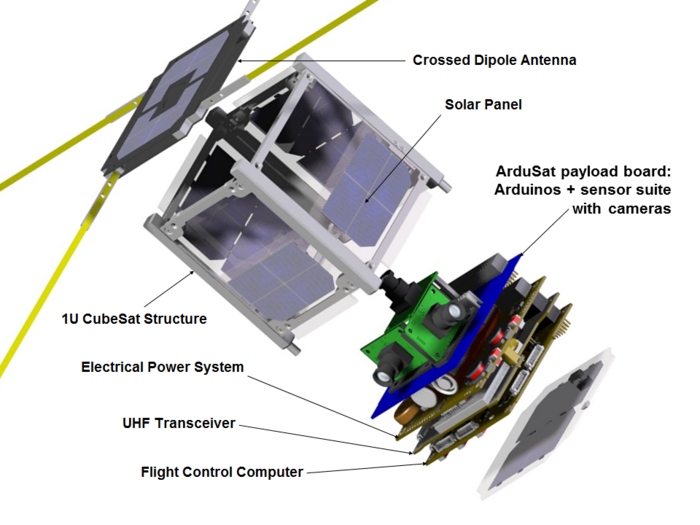

- ArduSat (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ArduSat) was another project in a series of open-source satellite launches in the early 2010s. It follows the CubeSat standard, just like Skycube. ArduSat contained a more expansive sensor package with a 3-axis magnetometer digital, a 3-axis digital gyroscope, a 3-axis accelerometer, one infrared temperature sensor, four digital temperature sensors, two luminosity sensors, two Geiger counter tubes, one optical spectrometer, and a 1.3MP camera. It also contained a UHF transmitter which allowed it to communicate with the ground. There were two versions launched on August 3, 2013, and November 19, 2013

- There are plenty of other satellite-based OS hardware projects in the works. For example, KickSat (https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/zacinaction/kicksat-your-personal-spacecraft-in-space). You just have to search and find them.

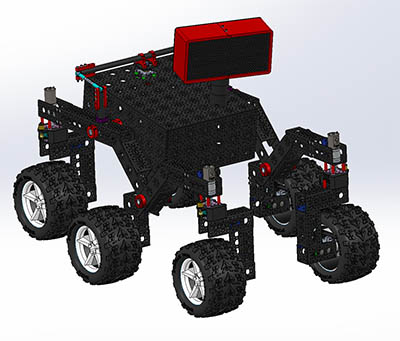

Of course, it’s not just satellite projects. LibreSpace has multiple open source projects in the works. From the SatNogs DIY Satellite Ground Station and Network program to the PocketQubes there are lots of options. However, the release of the Open Source Rover Project from JPL is one of the most recent developments. After multiple people requested more information about the design of the Mars Rovers JPL released a version of the designs in July of 2018 and posted the files to GitHub. Now, you too can print out the hardware pieces and make your own smaller version. Of course, you can also order the entire system pre-printed if you want.

These projects aren’t just standing alone. Many organizations are working to bring about the same concepts into the light. The Open Space Agency (http://www.openspaceagency.com/) and Libre Space, for example. Space Decentral is working on the Coral project to utilize regolith along with the Lunar Odyssey, Martian spring, asteroid commons, spaceship earth, future forwards, black sky, building blocks, our space, and Maximum Jailbreak media projects. Or how about the Team FREDNET group that’s working to compete in the Google Lunar XPrize competition.

The Living Universe Foundation can have a pivotal role in the development of these kinds of projects. Why? Because we have a more comprehensive vision that incorporates all the other kinds of projects. This is possible because of the open nature of these projects. We can either incorporate these designs into our projects or act as an umbrella organization gathering these disparate projects together and acting as mediators.

At the same time, we can work in areas that other organizations aren’t working on. Applying open source technologies to habitat design and ECLS (Environmental Control and Life Support) systems. This would allow us to extend those technologies to learning to survive on the earth, too.

How do YOU think we should expand our concepts in these directions?